How Easy works, part 2

Page originally created December 20, 2018

Page updated: November 12, 2022. April 2, 2023. April 8, 2023

How Easy works part-1 is here:

https://easyos.org/tech/how-easy-works.html

The layered filesystem

Recapitulating, here is a visualization from part-1,

showing the layered filesystem just after

bootup:

| / |

this is the abstraction, view at the top |

| RW layer folder |

this is a folder created in the RAM |

| RO layer folder |

easy.sfs is mounted on this folder |

As explained in part-1, the RW layer is a zram device in RAM, and it

needs to be saved to the .session folder, at any time while running

Easy, or at shutdown. Or, if you don't mind the drive being hammered

with writes, the .session folder can be mounted directly on the RW layer

folder:

| / |

this is the abstraction, view at the top |

| RW layer folder |

this is the .session folder in the working-partition |

| RO layer folder |

easy.sfs is mounted on this folder |

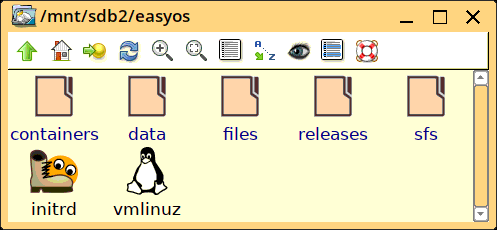

Also as explained in part-1, the image file that you download and

write to a USB-stick, has a vfat boot-partition, with Limine boot-loader

installed in it, and a ext4 working-partition, that has the EasyOS

files vmlinuz, initrd and easy.sfs.

At the first bootup, the initrd increases the size of the

working-partition to fill the drive, and creates some folders in it, and

moves easy.sfs into the sfs folder. This is what the working-partition

looks like after bootup:

Right-click in the window, the menu has an entry to show hidden files and folders (they start with a "."):

...showing the .session folder, where that RW layer gets saved, and the sfs folder where easy.sfs got moved to.

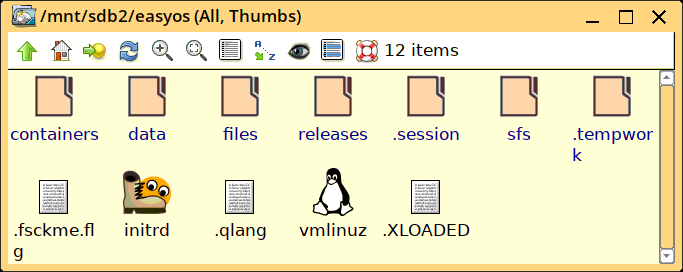

Part-1 also explained that the aufs layered filesystem has created

"/" with RW and RO folders underneath. if you start the file manager and

look at "/". this is what you see:

A way to conceptualize this "/" is to see it as an an abstraction, a contrivance, created in RAM.

If you were to create a file, say /usr/share/doc/test.txt. That will

actually be created underneath, in the RW layer, and if you choose to

save, will end up in the .session folder.

Or, if you do not save, it will disappear at shutdown.

However, there is one exception; the /files folder. That folder is

linked to the files folder in the working-partition, so anything created

under /files is actually created in the working-partition. From the

above example, that is /mnt/sdb2/easyos/files

To be more technically correct, /mnt/sdb2/easyos/files is "bind mounted" on /files

The reason for doing this is that most apps default to

open|save|download to /files, so if for example you save a web page from

the browser, or download a file, it will be saved under /files, so is

immediately saved.

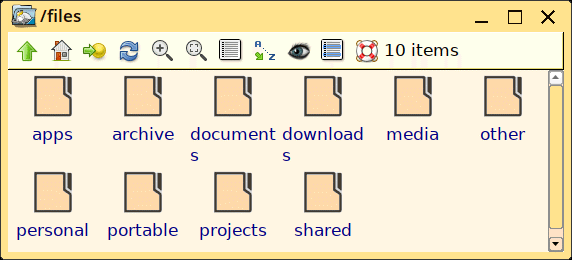

Thus, /files is the place for all your personal files. There is a folder hierarchy under /files:

Different apps will default to save in different places under /files,

for example mtPaint will default to save images to /files/media/images

Other special features of /files:

- Apps in containers are isolated from the main filesystem; however, /files/shared inside the container is linked to /files/shared in the main filesystem. This is a convenient way for an app in a container to export a file to the "outside world".

- Any app may be run non-root. For example, Firefox runs as user

"firefox", with home folder /home/firefox. Firefox does not have write

permissions outside its home folder; however, it does have permission to

save to /files

Now to examine further what is in the working-partition...

The working partition

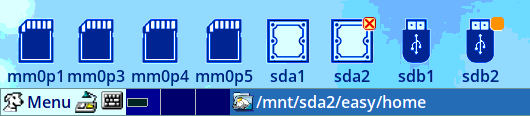

Staying with the example of booting off a USB-stick which is /dev/sdb, with sdb1 being the boot-partition and sdb2 the working-partition. Here is an example of how the partition icons will look on the desktop:

The solid-orange rectangle marks the working-partition, and under normal conditions it cannot be unmounted as it is in use.

The rectangle with a cross in it is a mounted partition that can be unmounted -- which is achieved by clicking on the cross.

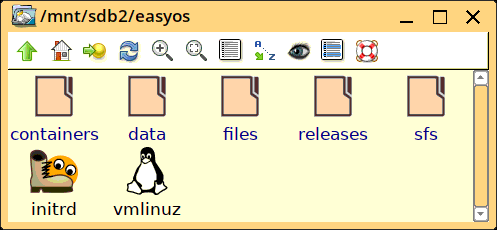

If you click on the sdb2 icon, it will open in the file manager, and you will see /mnt/sdb2, with folder easyos. Then if you click on easyos, you will see what is inside -- see snapshot back up this page. Well, here it is again:

Incidentally, that folder name "easyos" is an arbitrary name. It

could be any name, or deeper in the hierarchy, for example

"easyos/dunfell"

That folder name is variable WKG_DIR, that you can see in /etc/rc.d/PUPSTATE

The WKG_DIR is specified at bootup, in the limine.cfg boot-loader configuration file.

Here is a summary of some of those folders:

|

containers |

This is where applications can be run in isolation. Each

container is a layered filesystem, very similar to the

main one, with RO layer easy.sfs, and a RW

folder. Additional SFS files may be loaded as RO layers,

for example the "devx" SFS for compiling source packages

(Puppy users will know all about that!). Containers serve

two purposes, isolation and/or security. |

|

files |

Easy, like Puppy, is a single-user system. With Easy, /files is where you store all your "stuff".

Downloaded files, photos, videos, anything. And as previously stated, /files is actually a link to folder files in the working-partition. It is a work-in-progress to get the apps in Easy to open in the /files folder whenever "File -> Open..." (or Save, or Download) menu operation is performed. |

|

releases |

This is an archive for Easy versions and snapshots. For

example, if you upgrade from version 4.4.3 to 4.5, all

of version 4.4.3 is saved in folder releases/easy-4.4.3,

and you can at any time roll back -- the menu "Filesystem

- > Easy Version Control" handles this.

|

sfs |

All SFS files are kept in here, to keep them nicely categorised and avoid duplication. |

Note, there will be two more folders,

'appimage' and 'flatpak', that are created if an AppImage or a Flatpak

package is installed.

What follows are various usage technical topics. Not

exhaustive, and it will be helpful to read other web pages at easyos.org

Upgrade, snapshots, rollback

Upgrading, snapshot and rollback is now a separate tutorial:

https://easyos.org/user/easy-version-upgrade-and-downgrade.html

In a nutshell, it is very easy to upgrade and to rollback.

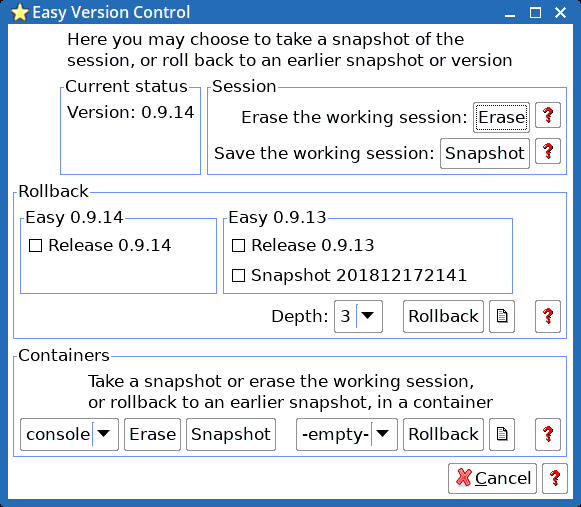

As the above link explains, there is a nice GUI to manager roll-back and roll-forward. Reproducing a snapshot here:

...which shows after upgrading from 0.9.13 to 0.9.14, and a snapshot

was taken in 0.9.13. Roll-back and roll-forward can be to any of these.

Obviously, saving a complete record of past versions is going to

occupy a lot of the working-partition. However, the history is

saved as compressed SFS files. To avoid the history growing to

fill all of the partition, there is a maximum depth setting, set

to "3" in the above photo -- meaning that only the current version

and two prior are kept. But any number of snapshots within that depth limit.

Another thing to consider, is that /files is outside

of this rollback/snapshot mechanism. /files is where you

can keep all your personal files. Downloads, videos, photos, etc.

Try and put as much as you can in here, instead of bulking up the

.session folder.

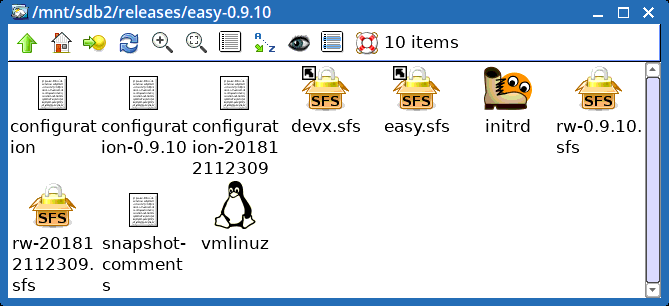

releases folder

All of the files belonging to a particular version of Easy are

in a sub-folder inside the releases folder, for example releases/easy-0.9.10.

If you were to look inside one of these sub-folders, this is

indicative of what you would see:

The configuration files have various configuration variables. SFS

file devx.sfs is familiar to Puppy users -- it

contains everything to turn Easy into a compiler environment, and

can be selected to mount as a layer at bootup. Extra SFS files

such as devx.sfs are optional, and can be selected

to be added to the layered filesystem at bootup.

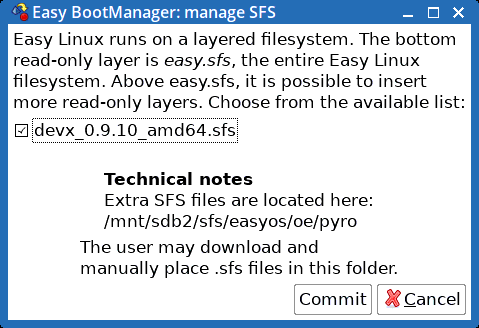

It is very easy to add, or remove, an extra SFS file to/from the layered filesystem: see the menu "Filesystem -> Easy BootManager":

...a ticked checkbox will mean it is already loaded.

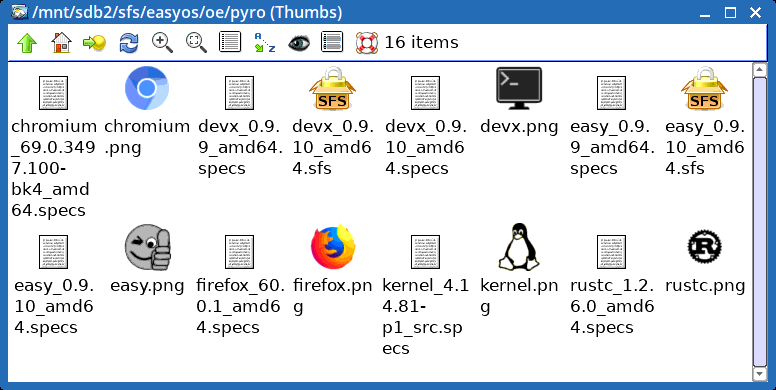

sfs folder

Notice in the above snapshot, the sfs folder, and in

second-from-last "easy.sfs" and "devx.sfs" are symlinks. The purpose of

sfs folder is to keep all of the SFS files organised, into categorised

sub-folders, and to ensure there isn't unnecessary duplication.

Here is a picture of one such sub-folder under sfs:

Downloading and installing of SFS files is managed via the "sfs" icon on the desktop.

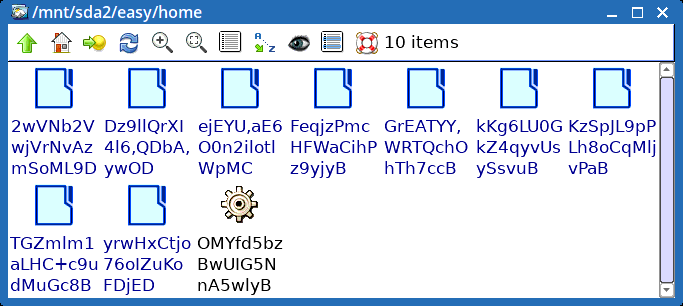

Encryption

The init script, the first thing executed at bootup, as

explained in part-1, has an option to encrypt folders in the

working-partition.

What the init script does, is ask for a password. If the user decides to provide one, then the containers, releases, home and .session folders in the working-partition are encrypted.

This can only be done when the folders are newly created, with

nothing in them. From then on, at every bootup, the password must be

entered to unlock them.

The encryption mechanism is provided for the ext4 filesystem,

using "fscrypt", which is a feature built-in to ext4. It provides

AES-256 encryption.

Note that the sfs folder is not encrypted. This is because

there is no point in encrypting the SFS files, and doing so would only

slow down operation.

So, what does a folder look like if you don't have the password to

unlock it? Here is an example::

Moving on, Easy is designed from scratch to support containers...

Easy containers

Easy has been designed as "container friendly". It was carefully considered how containers would fit in, that is, be highly integrated with the rest of Easy, extremely easy to setup and use, and be very efficient.

There are ready-made container solutions out there, such as LXC and Docker, however, for now Easy is built with a "homebrew" container. The Author is far from being a security or container expert, but for his own satisfaction wanted to play with containers created from basic principles.

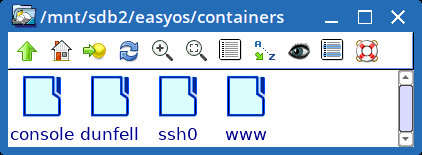

Starting by looking at containers already created in the currently running Easy. ROX-Filer shows the containers

folder in the working partition, for the Dunfell-series of EasyOS:

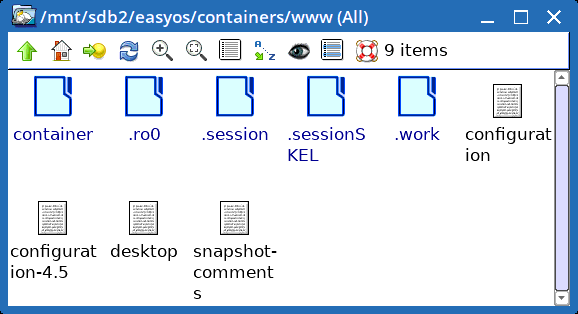

Burrowing down, looking inside the www

folder:

See also the "dunfell" container. This is a container for to run the entire Easy desktop in a container. It runs

as a layered filesystem, just like the main Easy filesystem, with easy.sfs on the bottom,

a read-write layer, and the

"top" (the container folder).

Well, Easy is setup so that dunfell, console and www are pre-created,

however, it is very easy to create a container for any application

-- there is a nice GUI, called Easy Containers.

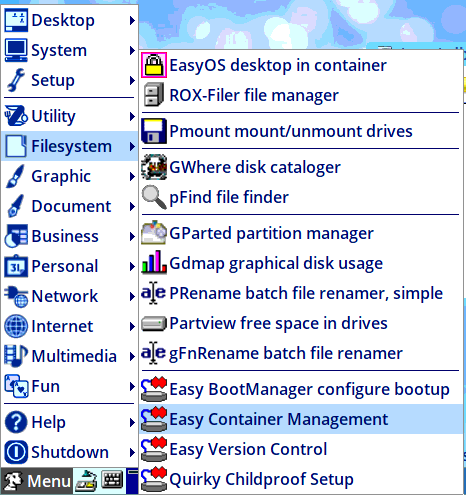

It is launched via the Filesystem menu:

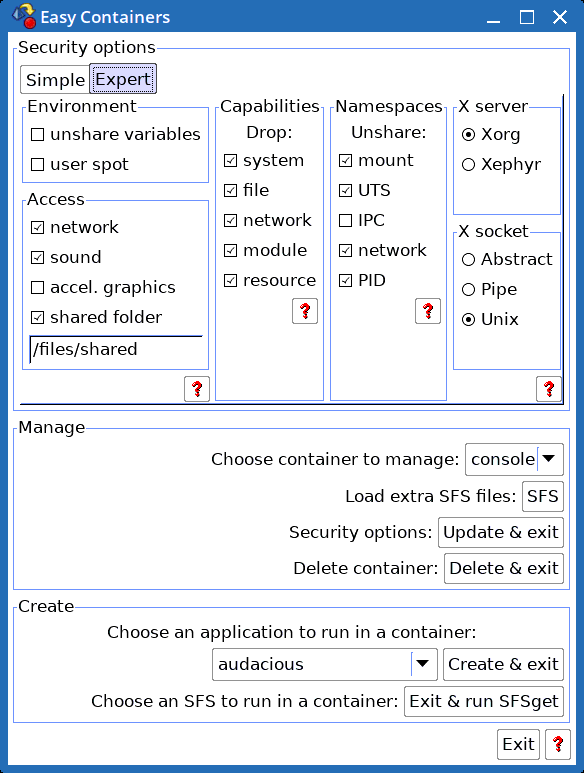

Here is a snapshot:

An existing container can have its behaviour modified, or be

deleted, as shown.

To create a new container, it is just a matter of selecting an app

from the drop-down list, choose appropriate security options, then

click the "Create" button.

There is help available for making the best decisions regarding

security, but also there are templates that will preset the

checkboxes when you choose an app.

Technical note: these templates are located at /usr/local/easy_containers/templates

A desktop icon is automatically created. These are the pre-created container icons, for the Dunfell-series:

|

And for the Kirkstone-series: |

|

...just click on an icon to launch it!

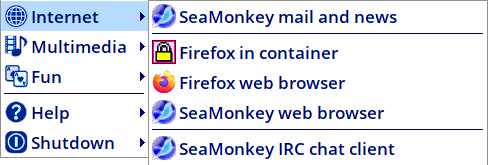

Furthermore, a new menu entry is automatically created, just like this one for Firefox:

...two Firefox entries. You can choose to run it

normally or in the container.

Note the special icon used to denote apps that run in a container.

Extra notes about Firefox security:

Even when running normally, on the main filesystem, it is running as user "firefox", so has the safety of being non-root. Also Firefox has its own sandbox. So this is one situation where running on the main filesystem might be almost as secure as running in a container.

There isn't anything more to say, that's it, container created and ready to use.

What actually happens if you select that containerized Firefox

entry in the menu, is that it executes "ec-chroot firefox",

instead of just "firefox".

ec-chroot is a script,

found in /usr/local/easy_containers/. In a nutshell, it will "start" the container, then chroot

into it and run the app.

By "start", it is meant that the layered filesystem will be setup. ec-chroot

calls another script to do this, named start-container.

When the app terminates, or the container is in other ways exited,

ec-chroot calls stop-container, which

kills all processes running in the container and unmounts

everything.

This technical description of container scripts is only mentioned if you are

interested. For someone who is just a user, the GUI does it all,

and very simply.

A note about the efficiency of Easy Containers. There is virtually

no overhead to add a container. No files are

duplicated. The same easy.sfs is used as for the main

Easy Linux.

Of course, running an app in a container, it will create its own cache files

and so on.

The container layered filesystem

What is the point of running an app inside a container? Thinking about the user, who isn't concerned about the technical details, just what practical benefits the container concept brings, or what problems.

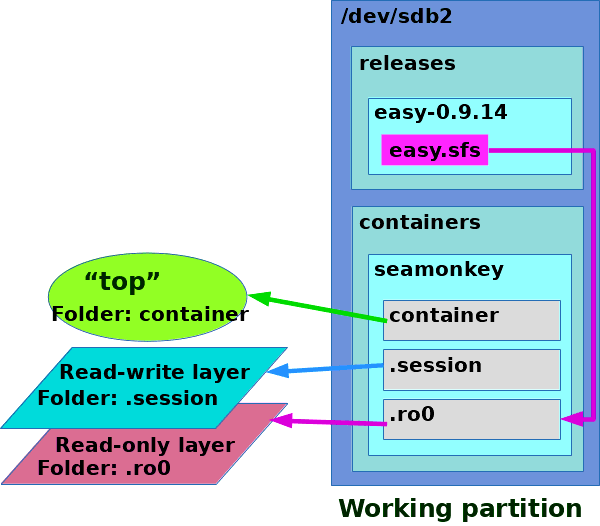

Broadly, there are two reasons, one, to provide isolation from the rest of EasyOS, and second, security. A diagram helps here, to show the filesystem you have access to while running in a container:

The example is for a container named seamonkey. easy.sfs

is mounted on folder .ro0 and this becomes the

bottom read-only layer (also, there can be more RO layers).

Actually, this example was written during the EasyOS Pyro-series, before

the Dunfell-series, and SeaMonkey was the default browser, builtin to easy.sfs. The Dunfell-series adopted Firefox as the default, builtin to easy.sfs, and now the latest, the Kirkstone-series has Chromium builtin.

If SeaMonkey, Firefox or Chromium was not builtin, it can be provided

as an SFS, in which case it can be mounted as another RO layer above easy.sfs.

The

folder .session is RW, and the user's view in the

running container is folder container. This was

already explained, however, think about it...

The app running in the container, or any file manager or terminal

emulator, will only be able to see the files in folder container.

Which is the content of easy.sfs and any changes made

on the rw layer. That's it, the rest of the system is just not

there.

Yet, as folder .session is just a folder in the

working partition, the entire storage area of the working

partition is available. If the working partition has, say, 14.5GB free

space, that's how much free space you will have in your container.

RW layer indirection:

To be entirely correct, the default behaviour is that the above diagram is not quite correct. Containers also have the same mechanism of mounting a zram device on the RW layer, so writes are written to RAM only. Exactly the same principle applies; when the session is saved, the RW layer is flushed to the containers .session folder.

And just like on the main filesystem, you can switch to direct writes to the .session folder; then the above diagram is correct.

This is all managed from the "save" on the main desktop; choose to save, and the RW layer will be flushed to the .session folder on the main filesystem as well as any running containers.

If you want to access files

created in the container, staying with the example of SeaMonkey in a container, just look at /mnt/sdb2/easyos/containers/seamonkey/container (equivalent to /mnt/wkg/containers/seamonkey/container) -- do this while the container is running.

Or, as already mentioned, an app inside the container can save to /files/shared, and it will also appear at /files/shared in the main filesystem. This sharing mechanism is optional and can be turned off if considered to be a security issue.

Extra thoughts about file access in containers:

Yes, an app can export a file via /files/shared, but think about the above two paragraphs. On the main desktop, you can look at /mnt/wkg/containers/seamonkey/container and see everything inside. Thus, you can access any file inside the container. So for example if SeaMonkey downloaded to /files/downloads in the container, no problem, you can grab it.

Looking into a container from the outside, you are like God looking down from the Heavens.

There are security options, that will impose further restrictions

on what can be done, with a view to keeping someone with

ill-intent from somehow accessing outside the container. This is

neat, but there is a downside. Some apps might not work, or not

properly, especially as more of the security options are turned

on.

SFSget

Reading the above might tend to cloud the understanding. EasyOS is

best "just used", that is, use it and you will find it is easy. It

becomes complicated when there is an attempt to explain everything that

goes on "under the hood".

Yes, the Easy Container Manager, snapshot above, can turn any app into a containerised app. Great.

There is also an online repository of SFS files, and these can be

downloaded and run in containers. These SFS files can be individual apps

or complete distributions.

The dunfell container (or kirkstone container in

the lastest series), described above, is an example of a complete EasyOS

running in a container, as a separate window.

There is an icon on the desktop, labeled "sfs", click on that and

you can access the online SFS repository. This link is an example,

showing downloading of Xenialpup 7.5, a complete Puppy Linux distro:

http://bkhome.org/news/201811/xenialpup-75-running-in-easyos.html

So, yes, read these technical pages, but do go and actually do it, to appreciate the simplicity.

If you would like to learn more about the online SFS repository and

even how you can create your own SFS repository that SFSget can access

-- with a view to making it available to others -- please read this blog

post:

https://bkhome.org/news/202003/sfsget-now-much-faster.html

...you would also need to learn how the 'dir2sfs' utility works, see here:

https://easyos.org/dev/coding-for-easyos.html

More technical usage highlights

it is planned to insert a few more introduction topics here. Or maybe a "part-3".

Tags: tech